August 19 is also the Traditional Day of the People's Public Security - the traditional day of songwriter Xuan Oanh's family: His wife, Le Thi Xuan Uyen, is the first female spy of the Hanoi Police. He has three sons, one works as a businessman and two are in the police force, General Do Le Chau and General Do Le Chi.

However, his "big world" was the field of people's diplomacy, sensing, and mobilizing international public opinion, including American pilots detained at Hoa Lo in the last years of the resistance war against the US to unify the country.

Thomas Wilber - son of US pilot Gene Wilber, who was at Hoa Lo for nearly five years until early 1973, said that he wrote this article "from my heart and mind" to let people see more clearly the "people-to-people diplomacy" part of Xuan Oanh's life in the eyes of Americans. The article will be published in the book "Do Xuan Oanh - the oriole of the Revolutionary Spring", in the anniversary of his 100 birthday, by the National Political Publishing House - Truth this autumn.

* * *

|

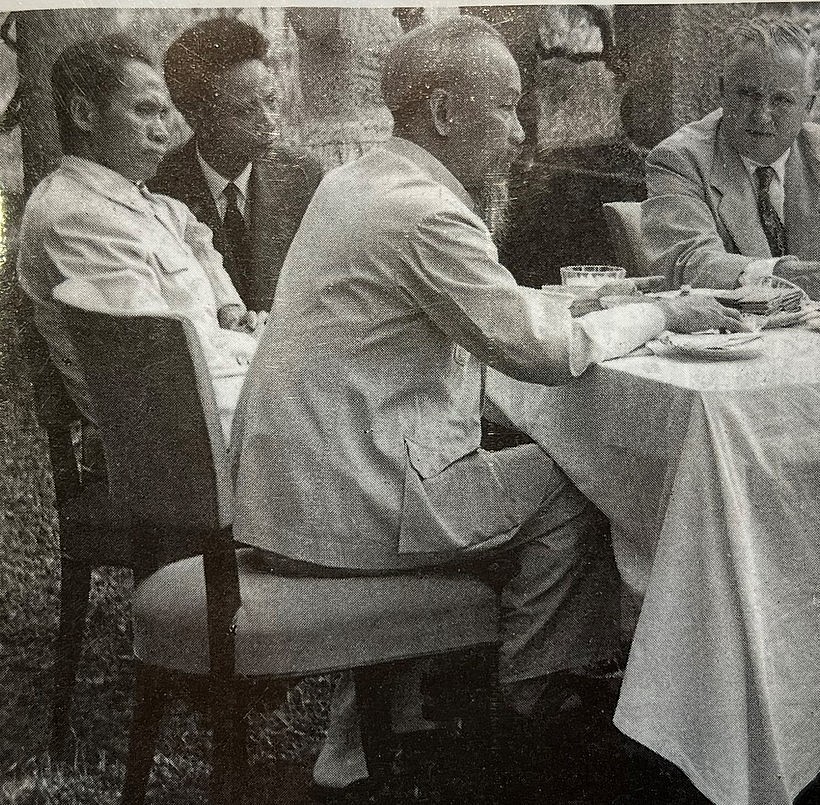

| Xuan Oanh (2nd from the left) interpreted for Uncle Ho and Prime Minister Pham Van Dong (Photo courtesy of the family) |

The United States abetted the re-introduction of Western imperialism to Indochina when President Truman decided to retreat from a movement toward a post-colonial, post-imperial world. Disregarding the promises of his predecessor Franklin Delano Roosevelt for a post-War era dedicated to ending imperialism, Truman heeded his European-influenced advisors along with the restored French government under de Gaulle to allow France to seize back its pre-War colonies.

Truman authorized the American military transport of French troops to Indochina in the weeks after the end of the Second World War and the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Imperialism in Southeast Asia again had a foothold, with U.S. government assistance. A lengthy war funded and supported by the United States culminated with the defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu in May of 1954.

Ongoing and unwanted American involvement fostered a polarizing political situation in Vietnam throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s. Eventually, this difficult situation became horrific in scale and scope, devolving to direct, violent military aggression.

|

| Tom Wilber during a visit to Xuan Oanh's house in Quan Su in 2023. |

As these military actions by the United States against Vietnam increased alarmingly in the mid-1960s, Ho Chi Minh asked Do Xuan Oanh to assist in making the case internationally to peace organizations and nongovernmental organizations alike to influence their governments to apply pressure on the United States, urging the withdrawal of military forces and the negotiation of an end to hostilities.

Such pressure exposed how the actions of the United States government impeding the implementation of the 1954 Geneva Agreement and preventing democratic elections in 1956 were unwarranted interventions that escalated into the violence that the world was now witnessing. This massive intimidation was being exerted by the most powerful military in the world, threatening the independence and freedom of the small, third-world country of Vietnam. It was Xuan Oanh’s role to develop international witnesses sympathetic to and supportive of the independence and freedom of Vietnam, to convince the United States to cease their undeclared, and illegal, warfare in Vietnam.

From 1964 to the 1973 American withdrawal, Xuan Oanh performed key roles in several arenas, including (people-to-people) diplomacy, coordinating visiting international delegations, and even assisting with the management of the population of prisoners held by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the Hanoi prison sites.

In these wide-ranging arenas Xuan Oanh was acknowledged by those who interacted with him for his savvy, artistry, communications skills, diplomacy, and – above all – his humanity, in representing the interests of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam all the while communicating these interests in a manner that was both convincing and disarming to the westerners with whom he interacted.

One could argue that Xuan Oanh exhibited a high degree of emotional intelligence coupled with the powerful intellect he developed through self-learning, without the help of formal education.

After U.S. military incursions by air against North Vietnam began in August 1964, Xuan Oanh traveled in Asia and Europe representing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam at international peace conferences and among key diplomats in many countries. He urged governments and their citizens to join with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam to condemn the United States government for its acts that were now manifesting in air attacks against the Vietnamese people.

Among these international peace constituencies that Xuan Oanh met in his travels were American activists, many of whom would later travel to Vietnam to convey the support of American citizens and learn how to better address their concerns for peace to U.S. government officials along with the American public. Nearly all these peace groups interacted with Xuan Oanh in their pursuits of various paths to bring the war to an end.

American authors from this period in the 1960s and ‘70s document some of their interactions with Xuan Oanh. Travelers from America made the challenging trek to North Vietnam as early as 1965, working around U.S. State Department bans to prevent American citizens from making such trips. By the time of the American withdrawal, some 200 U.S. citizens made the trip, some many times. Some peace activists, such as John McAuliff, landed in Hanoi on the day the Paris accords were signed. A common set of experiences among these many peace travelers spanning seven or eight years were their open and engaging interactions with the people of Vietnam through their host, Xuan Oanh.

In her book Traveling to Vietnam: American Peace Activists and the War, Mary Hershberger notes that “Xuan Oanh was an interpreter for Aptheker, Lynd, and Hayden during their Hanoi visit December 28, 1965, through January 6, 1966.” Activists Staughton Lynd and Tom Hayden detail this trip to North Vietnam in their book The Other Side: Two Americans Report on Their Forbidden Visit Inside North Vietnam (New York: The New American Library, 1967). They refer to Xuan Oanh and the important roles he played not only as an interpreter and communicator but as an explicator of the rich culture and heritage of Vietnam.

It seems the findings of their trip benefitted from the perspective that Xuan Oanh gave these activists who were deeply experiencing Vietnamese culture for the first time. Coupled with his knowledge of American culture and history, Xuan Oanh was uniquely qualified to point out cultural differences and explain them in a way that Americans could understand, providing insight not only on the Vietnamese culture but, in reflection, on their own.

Lynd and Hayden’s observation illustrates Xuan Oanh’s notable characteristics:

Knowing Oanh gave us an intimate view of Vietnamese culture and social life. His nationalism was individualist and passionate. As we walked along the lake one evening, he began to talk about Vietnamese culture. The language, he reminded us, is such a poetic language that common dialogue becomes verse. It is a delicate and precious language, he said with great pride, “much harder to learn than Chinese.” This culture, we came to understand, is yearning to be liberated from years of obscurity caused by the domination of larger powers.

Lynd and Hayden were impressed favorably not only by Xuan Oanh’s knowledge but his manner of conveying it to them, resulting in understanding. In his 1988 work titled Reunion: A Memoir, Tom Hayden further explained his understanding of Xuan Oanh’s role, not only as a guide developing good relationships with peace movements and nongovernmental visitors from other countries but as a person with a desire to “educate his own country favorably about America.” Hayden learned in the debate with Xuan Oanh about this point that the purpose of educating “to reduce hatred” was strategic. Distinguishing American citizens from their government’s administration and policy could be a positive force on public opinion.

Based on his trip to Hanoi in the late spring of 1972, Bill Zimmerman recalls Xuan Oanh as “a western-educated and urbane official who traveled frequently in Europe and served as a roving ambassador to…(the) antiwar movement.” As early as 1965 and as late as 1972, peace activists consistently reported on the beneficial information Xuan Oanh provided as their host. That is not to say that these visits were social activities. Beyond these humane and sociable manners of behavior were the sovereign interests of a nation determined to break the yoke of those nations who would act as oppressors.

|

| Cora Weiss, former President of the Association of American Families with relatives detained in Vietnam, a close friend of Xuan Oanh, secretly relayed correspondence between American pilots at Hoa Lo and American families in the 1960s-1970s. |

These visiting activists were experiencing in real and practical ways the idea of “people-to-people diplomacy” that Ho Chi Minh had in mind when he set up myriad “Friendship Associations” beginning with the Viet Nam – America Friendship Association in the earliest weeks of the newly formed and independent Democratic Republic of Viet Nam. The Viet Nam – America Friendship Association came into being on October 17, 1945, followed by a tea party reception to recognize this spirit of rapport. The Democratic Republic of Viet Nam was merely 45 days old but would soon form many bilateral friendship organizations of the Vietnamese people with the people of other countries. It is noteworthy that the Viet Nam – America Friendship Association was established first.

Sadly, the active status of the Viet Nam – America Friendship Association would soon pause its public operation. In the early months of the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam, the French tried by force to re-occupy Vietnam, as well as Laos and Cambodia, receiving financial and military support from America. However, The Democratic Republic of Vietnam thwarted those efforts in May of 1954 at Dien Bien Phu. During that time the Viet Nam – America Friendship Association was not publicly active, and not to become active again until the Paris Peace negotiations would begin in the latter 1960s, with a new name to reflect the focus on the key relationship with the people of an aggressor nation – The Vietnam Committee for Solidarity with the American People. Xuan Oanh’s job title was Secretary, Vietnam Peace Committee, Vietnam Committee for Solidarity with the American People.

Years after the American War, the organization would become active again, initially to bring about the conditions for the normalization of relations between the two countries with a new name that persists today – The Vietnam-US Society, part of the Vietnam Union of Friendship Organizations. This history, coupled with the precedent of positive interaction with the people of other countries, was a pillar of diplomacy in Vietnamese culture and would become the basis for Xuan Oanh’s engagement with American visitors, aligning well with the appeal for “solidarity with the American people.”

David Dillenger’s 1966 Hanoi visit included many interactions with Xuan Oanh who helped Dillenger call on many of the peoples’ constituencies in North Vietnam including the youth organization, the women’s organization, labor and agricultural organizations, and more. With Xuan Oanh as his guide, Dillenger was able to have rich and challenging discussions triggered by his often-difficult questions.

Xuan Oanh helped Dillenger with wide-ranging access from farms to factories and the highest levels of government:

“My friend, Do Xuan Oanh, who wrote the Vietnamese national anthem, a poet and a musician, was my interpreter and had been my interpreter on most of my trips to the countryside and so forth. He was my interpreter that day. I was sitting and talking to Pham Van Dong when all of a sudden, Ho Chi Minh walks in. He stood there and smiled. We talked.”

Dillenger continues to describe some details of this fascinating dialogue. Imagine an American peace seeker sitting in a room with Xuan Oanh and Pham Van Dong, engaging in a constructive discussion while speaking freely with President Ho Chi Minh. Of Dillenger’s takeaways from that interaction, two should be mentioned here. Firstly, regarding the prisoners of war, Dillenger quotes Ho Chi Minh as saying, “We feel very sorry for them. We want to treat them very well and hope that they go away from here better citizens or with better understanding than when they came here.” Secondly, Dillenger quotes Ho Chi Minh as saying, “We have no quarrel with the American people. Our quarrel is with the administration.” Dillenger realized he had witnessed how this message had reached the many organizations he had met with over the prior days of his visit. Dillenger’s experience was one of the great rewards of people-to-people diplomacy which was, again, the basis for the first Viet Nam – American Friendship Society, and the mission that Xuan Oanh worked to fulfill despite these critical years of violence and aggression.

|

| Merle Ratner, a member of the US Communist Party, holds a photo of Xuan Oanh at her home in New York, USA, in 2022. Ratner has dedicated her life to Vietnam. She is the co-founder and coordinator of the Vietnam Agent Orange Relief & Responsibility Campaign (VAORRC). (Photo taken at Ratner's home in New York, USA, 2022). |

In 1967 Tom Hayden led a group of American peace activists to attend a conference in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia that brought U.S. antiwar advocates together with representatives of the North Vietnamese government and the National Liberation Front (NLF), whose attending delegation included Madame Nguyen Thi Binh. Xuan Oanh conveyed the invitation for the group of Americans to come to Hanoi at the conclusion of the Bratislava Conference. Six of them made the trip to Hanoi including Hayden. Among them were Carol McEldowney and Vivian Rothstein who both kept journals and wrote numerous entries about their interactions with Xuan Oanh during their several days visit to learn about Vietnam first-hand.

As did many such peace travelers, McEldowney and Rothstein noted the qualities of Xuan Oanh that helped them get the most out of their visit. Xuan Oanh was able to present and explain eastern culture in a way that westerners could begin to grasp. McEldowney noted some particulars about Xuan Oanh that reflect his humanity that strikes a chord with westerners. She made a note that “Oanh brought his five-year-old son, Chi, to a music troupe concert on October 1, 1967." If American propaganda mythology against its chosen enemy tried to “Otherize” the Vietnamese in some ugly way, the humanity that American peace activists noted in their travels contradicted that myth and humanized the Vietnamese in a subtle but powerful, and enduring, way.

THOMAS (TOM) WILBER

-------------------------------------------------------

Thomas (Tom) Wilber was born in 1955 and currently lives in Connecticut (USA). His father is US Navy pilot Gene Wilber. Gene Wilber's plane was shot down in the sky over Nghe An in 1968. Tom went to Vietnam many times, looking for witnesses, information, and documents about his father and his teammates to prove to the US public that what his father spoke the truth about the humanitarian policy of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government towards American prisoners of war, which was skeptical and criticized by the US public for a long time.

When returning to the US, Wilber himself was estranged from the US government and a part of the US public opinion because he told the truth. Wilber met Xuan Oanh at Hoa Lo Prison from 1971 to 1973.

---------------------------------------------------------

1. Carol McEldowney, Hanoi Journal 1967 (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 36.

2. James W. Clinton, The Loyal Opposition: Americans in North Vietnam, 1965-1972 (Niwot, Colorado: The University Press of Colorado, 1995) 48.

3. Bill Zimmerman, Troublemaker: A Memoir from the Front Lines of the Sixties, (New York, Doubleday, 2011), 267.

4. Tom Hayden, Reunion: A Memoir, (New York: Random House, 1988), 184-5.

5. Mary Hershberger, Traveling to Vietnam: American Peace Activists and the War (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1998), 41.

6. Staughton Lynd and Thomas Hayden, The Other Side: Two Americans Report on Their Forbidden Visit Inside North Vietnam (New York: The New American Library, 1967), 61.

7. Karín Aguilar-San Juan and Frank Joyce, editors, The People Make the Peace: Lessons from the Vietnam Antiwar Movement (Charlottesville, Virginia: Just World Books, 2015), 22.

8. Judy Gumbo, Yippie Girl: Exploits in Protest and Defeating the FBI, (New York: Three Rooms Press, 2022), 192-196. Gumbo reports a more precise number short of 200: “Only 174 people from the United States visited the former North Vietnam while the war raged.”