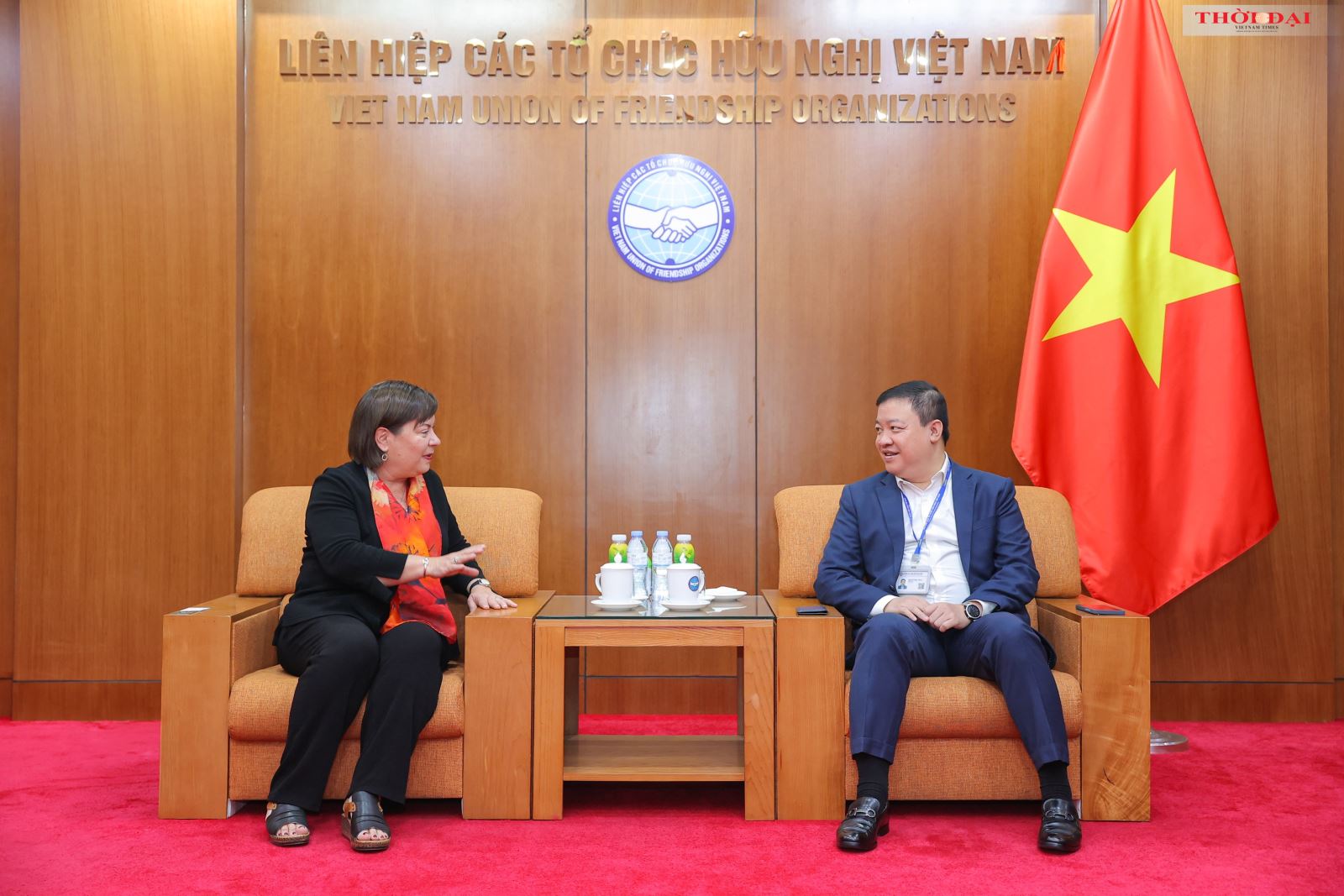

LEFT: Navy veterans Tom Wilber and his father Gene Wilber just before participating in the 2015 Memorial Day parade

Six years ago, on Memorial Day, I helped my dad assemble the many pieces of his service dress white uniform. As retired military, the local organizer had asked us both to ride on a float in our hometown parade. Why us? We represented two successive generations of naval careers.

Before leaving for the parade, Dad and I stood side by side for photos with the things that we carried. I held the remaining piece of his F-4J aircraft that I had collected two weeks earlier, in a village in Nghe An Province in north central Vietnam, where Dad’s burning fighter plane had crashed in 1968. The engine piece had spent decades re-purposed as a pot to hold flowers for Tet, the lunar new year family holiday in Vietnam.

Cast as a villain on his return

My dad, Gene Wilber, ejected from his plane two seconds before it plowed into an open field. Sadly, his backseater – a 24-year-old husband and father – was unable to escape the crash on that Father’s Day in 1968. Forty-seven years later, Gene held in his hand a small bottle of earth that I had collected from the crash site – the final resting place for his friend, Bernie. We carried these remembrances in the parade that day in 2015.

That was Dad’s final Memorial Day. Three weeks later, Gene was diagnosed with stage four brain cancer. Two weeks later, he died. The jet engine piece was again transformed into a flowerpot, this time displayed at his funeral.

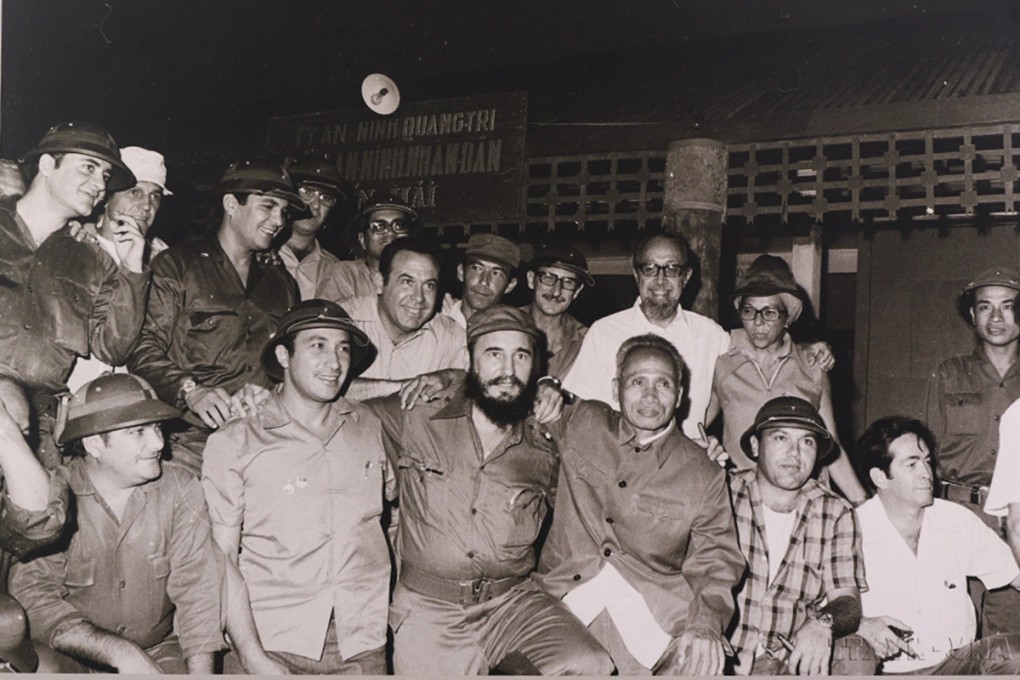

Standing upright during his final days was difficult for Gene, but he had always stood out, even as a prisoner of war. An experienced career aviator and fighter squadron commanding officer, he had thought he would be fighting for peace in Vietnam. But he felt the doubts looming even before he was shot down. In Hoa Lo Prison in Hanoi, the first 20 months of solitude afforded him the time to think deeply. Gene concluded that the war was illegal and misguided, and he believed that wholeheartedly for the rest of his life.

Most of the other POWs who turned against the war felt they had to suppress their beliefs, worried that if they said anything they would harm their careers, or, worse, be jailed on their 3 return. But my dad spoke against the war, during and after captivity. For him, conscience was paramount. The war was wrong. If he did not speak out, his silence would be a self-betrayal. Dad paid dearly for his dissent. Nearly five years a prisoner, he returned home to be cast as a villain among the many others who were scapegoated for the embarrassment of America’s Vietnam incursion. In 1973, the Nixon administration deftly orchestrated Operation Homecoming, welcoming returned POWs as the embodiment of “peace with honor” and creating an open season on dissenters.

Defend the Constitution, not your boss

To answer the war’s critics, the new narrative has made it easier throughout the decades since the war to blame America’s defeat by a lesser power on dissenting POWs and the broader antiwar movement. By the time Operation Homecoming rolled out, hundreds of thousands of Americans had marched in the streets, including tens of thousands of active-duty GIs and veterans. Avoiding the questions that Gene Wilber and other dissenting POWs asked, or completely unaware of their voices of dissent, our culture remains bound to an errant past, left only with a hero-myth. This dooms us to forever repeat Rambo’s cry, “Nothing is over!”

If Gene Wilber were to convey a message to military members and their families on this Memorial Day, what would it be? He was not anti-military. He saw a need for defense. He 4 volunteered for the Navy and flew over 200 combat missions in Korea and Vietnam. If he were here today, he would likely say this: Support and defend the Constitution, as that is your job. Remember that your truest loyalty has to reach beyond immediate boss, beyond chain of command, even beyond institution, to the principles that our country was founded on. Keep conscience clear.

Tom Wilber, an independent researcher investigating U.S. prisoners in the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam from 1964 until 1973, is co-author with Jerry Lembcke of "Dissenting POWs: From Vietnam’s Hoa Lo Prison to America Today." He retired as a Navy commander with 20 years in supply logistics with submarines, ships and aviation.

T.h / USA Today